Share Your Memory of

Jules

Obituary of Jules Cohen

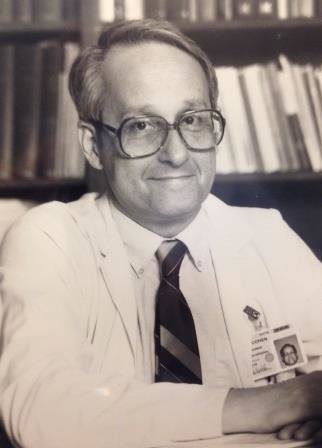

Jules Cohen, M.D.

October 8, 2015 at 84 years old. Predeceased by his favorite imaginary uncle, Itzhak. Survived by his loving wife of almost 60 years, Doris; devoted children, Rabbi Stephen (Marian) Cohen, David (Elizabeth) Cohen & Rabbi Sharon (Shimon) Cohen Anisfeld; adored grandchildren, Rachel (Zachary), Aryeh, Molly (Andres), Ethan, Simcha, Daniel & Talia & a community of friends & colleagues.

Dr. Cohen was a Cardiologist, Chief of Medicine at Rochester General Hospital & Senior Associate Dean at the University of Rochester School of Medicine.

Funeral Services will be held on Friday, October 9, 2015 at 1:30 PM in the Benjamin Goldstein Chapel of Temple B'rith Kodesh (2131 Elmwood Ave.). Click here for directions. Interment, White Haven Memorial Park.

The family will receive friends at the Summit at Brighton (2000 Summit Cir. Dr.) on Saturday from 7-9 PM & Sunday from 2-4 PM. Click here for directions.

Eulogy for Jules Cohen, MD

Delivered by Rabbi Steve Cohen

Friday, October 9, 2015

Our father, Jules Cohen, grew up on Vienna Street near Joseph Avenue, Rochester’s now vanished world of Yiddish, kosher delicatessens, butchers, bakeries, and fishmongers. His father Samuel had died when Jules was an infant, so Jules was an only child, raised by his mother Dora, known as Ducky, and a troop of additional parents, Ducky’s brothers and sisters Alice, Ben (after whom this chapel is named), Louis, Ida, Oscar, and Itch and their husbands and wives.

All these relatives, but not much in the way of money. Jules and Ducky lived with her unmarried sister Aunt Ida and her father, Max, Jules’ grandfather, a tailor. Every Saturday night the aunts and uncles and cousins would gather at the house on Vienna Street for dinner and Uncle Itch and Aunt Bert would stay overnight. Itch and Bert had no children of their own, and Itch schlepped Jules to the various shuls around town; he was an insurance man and needed connections everywhere! And Itch showed Jules how to do repair work around the house, instilled in Jules his love of hiking and camping, including in the snow of winter. And when Jules brought his report card home, Aunt Bert would look it over and demand: “what is with this A-??” Much was expected of this only child.

While still in High School, he began thinking about medicine and got a job with Mr. Yalowich the pharmacist, who allowed him to compound ointments, while hovering over his shoulder like an eagle. Jules’ boyhood best friend was Earl Cohen. Earl and Jules sat for hours by busy intersections, doing the apparently important work of writing down license plate numbers [correction: at this point in my delivery, my mother Doris shouted out “no, that was Jerry Viener!” who was in the chapel for the funeral. I apologized to Jerry, and acknowledged him as the partner in the important work of writing down license plate numbers and then continued], and with Earl, Jules talked about setting up a medicine practice together, Cohen and Cohen. That dream came crashing down when Earl died young, in the second year of medical school.

It took me years to understand that my dad entered adulthood in a blaze of accomplishment, and attended by a series of staggering losses. His gentle and funny mother Ducky was stricken with Alzheimer’s and became violent before they treated her with thorazine; Jules’ last glimpse of his mother was as a small, unrecognizable withered body curled up in a crib. In a single year, Alice died, and Ida, and Ducky, and Ben…and Itch developed Parkinsons. His best friend Earl died. And in the same short two-year span he got married, and began medical school and he and Doris had their first child. How does a young man survive a year like that?

Speaking of Doris. They first met in college at the U of R and went to the Senior Prom together. Doris had her 10-year-old brother Fred moved into Jules’ Sunday School class. Many years later, one of Fred’s friends told me: “all of us were in awe of your mother. She was brilliant and so beautiful.” When Jules began to date Doris seriously, after a few less satisfactory girlfriends, Uncle Ben said, “It is about time.” The family was pleased with Doris.

It was a long courtship, four years before getting married, and they did split up for a couple of months. Then one day Doris called and said “We better get married… before I change my mind.” That was almost 60 years ago. Over the past few days, including on the last day of my father’s life, it has felt important to ask: was this a good marriage? In their home there has been shouting and painful silence. And much music and tons of laughter. Arguing, struggling, embracing, wrestling, nurturing, nagging, ignoring, hurting, and healing.

Some of you might not be aware, but my parents are two gigantic personalities who have spent the past nearly sixty years together, like twin stars burning and turning and bound inextricably together. On Wednesday, after 60 years, my mother and David and Sharon and I sat in the presence of her twin star fading and flickering, and we debated what grade to give their marriage. Of course, mom demanded: “The truth! With no grade inflation!” I said: “You had a good marriage.” And Mom shot back: “So you don’t agree with C+?” No, I’d say it was a fiery, demanding, difficult and exquisitely tender marriage.

Sharon and David and I grew up in a home rich with culture, literature, political discussion, Jewish religion, guests for dinner (medical students from all over the world), and complete parental consensus about the rules: except in the event of nuclear attack, we all had dinner together at 6:30 every evening. And no matter how cold it was outside or how deep the snow, the kids were to get outside into the fresh air. Our entire childhood can be distilled into an intense recurring memory of our entire family piled onto a toboggan with our dad on the back steering, and hurtling down the sledding hill at Indian Landing School and then coming home to strip off our dripping clothes and gather around a bowl of popcorn and hot chocolate and the fireplace.

Then, in the long summer evenings, when we and the twenty or thirty kids of our neighborhood ran through the street, up to the school playground, or through the yards behind the houses, playing capture the flag or kick the can, when bedtime finally arrived, our Dad would step outside and blow three sharp whistles….the call of a red cardinal…which carried through the night and called us home. His whistle was the perfect thread of connection—allowing total freedom, and complete security all at once.

Like all children, we knew vaguely but not in any detail about our father’s world of work. So we are forever indebted to Stephanie Brown-Clark who in 2006, conducted a series of interviews with Jules about his life and his career, and to his secretary Amy Gregory, who turned the whole thing into a manuscript. Much of that memoir can be read as an extended meditation on the mysterious interplay between doctoring and teaching.

I’m sure I am not the first to notice that Jules embodied the biopsychosocial model of medicine. The biopsychosocial model, developed by his mentors George Engel and John Romano, focuses upon the three-way interplay between a person’s physiological health, their psychic health and their relationships with the people around them. Dad believed in this model, and he lived it. He brought to his patients not only a powerful analytical mind, but also a huge, empathic, knowing heart. He loved his patients and they loved him. His own experience as a physician confirmed for him over and over the inseparableness of body and soul; it was impossible to attend to one and not the other.

And it was the same with his students. Jules knew that education, like healing, only happens in relationship. Our Jewish tradition teaches this truth: Torah, which means teaching, is rooted in love; in ahavah rabbah. In love we receive wisdom, knowledge and tradition from our parents, and our teachers. And in love we transmit teaching to our children and students. Dad is quite candid in the interviews with Stephanie that research was never really his calling. He says he knew that research productivity was essential to make it in academia, but all he really wanted to do was teach! There were two reasons, he explains: first,…the tremendous satisfaction of helping the young come to an understanding. That was very gratifying. The other part is, according to Jules, it is nice to be told how wonderful you are! This was one of his guilty pleasures.

In 1975, Dad was recruited to become Chief of Medicine at Rochester General Hospital, and he remembers John Romano telling him “if you want to be loved every hour on this job, this is not the job you want.” When Stephanie asked Dad if John was right, he replied “It was important to me to be loved most hours of most days.” He often laughed about what he considered his narcissistic side, this “need to be loved,” but in the next breath he explained that he could only do medicine and education in the context of meaningful, healthy relationships.

In 1982, Dad returned to the Medical School, where as Senior Associate Dean for Medical Education he led a process of curriculum change. In his memoir, he remembers a comment made by John Leddy, who told him: “You know the thing you have that makes it possible for change to take place? You are tough, you are very strong, you are very determined, but you are very funny, you tell all these stories and people love it.”

Near the end of his fifteen years in the Dean’s Office, Dave Stevens, Vice President of the American Association of Medical Colleges came for a site visit and at the end of the visit Dave said: “Jules, I hope you know your DNA is sprinkled all over this place.” Jules told Stephanie: “I will never forget that.” I do not know if I ever shared with him that when he retired, Stephanie commented to me: “He is the soul of this medical school.” I hope that someone told him that.

I would like to close with a pair of stories which I think illustrate my father’s deepest medical instincts. He was once on a research team led by another of his mentors, the great cardiologist Paul Yu. Dad’s part of the project involved work with dogs. With characteristic self-deprecation, Dad comments: “my part was probably the least productive of any.” But then he added: “I did make one interesting observation... Whenever a dog had been subjected to a myocardial infarction, two of us stayed with the animal all through the night…and we didn’t lose a single dog. Eventually, we were totally worn out so we had to stop doing that. As soon as we stopped spending the nights with them, every dog died.”

The memoir then turns to the first Intensive care Units in Rochester. After the first Surgical ICU was built, he says, “one of us young people, either one of the fellows or one of the junior faculty, slept next to the patient for the first several nights after surgery. I think the presence was more important than anything we did.” Those were Jules’ words: “I think the presence was more important than anything we did.”

I doubt that many doctors have spent the night sleeping next to their patients, or researchers spent the night sleeping with the animal subjects of their experiments. But these stories of night-times together reveal my father’s insight, perhaps his most deeply held conviction. My dad knew intuitively and reflected throughout his life and career upon the divine, healing power of personal presence.

Of touch, of glance, of voice, of smile and laugh.

These were the most important items in our father’s medical bag.

For us--his family, for his patients, for his students and his colleagues, the memory of Jules Cohen’s loving, teaching, healing presence will be a blessing for the rest of our lives. Zecher tsaddik livracha.

Home

Brighton, New York

Birthplace

Brooklyn, New York

Donations